The Rising Cost of College Dining

“Like many college students, I have a full bookcase and an empty fridge.”

In a March 2017 Op Ed, Olivia Ellison–a senior at University of Colorado majoring in Exercise Science–shares her experience and thoughts on an alarming C&U student trend: food insecurity.

Ten years ago, Georgia State University officials became worried about the impact of pricier student housing on the ability to afford earning a degree. Research was commissioned to examine the connection and the results were sobering: for every $5,000 in unmet financial need, a student was 12 percent less likely to graduate[1].

As the higher education industry faces declining undergraduate enrollment and falling numbers of high school graduates, basic and affordable amenity options are quickly becoming top priority with C&U leadership looking to attract increasingly cash-strapped students and their families.

WHY IT’S HAPPENING

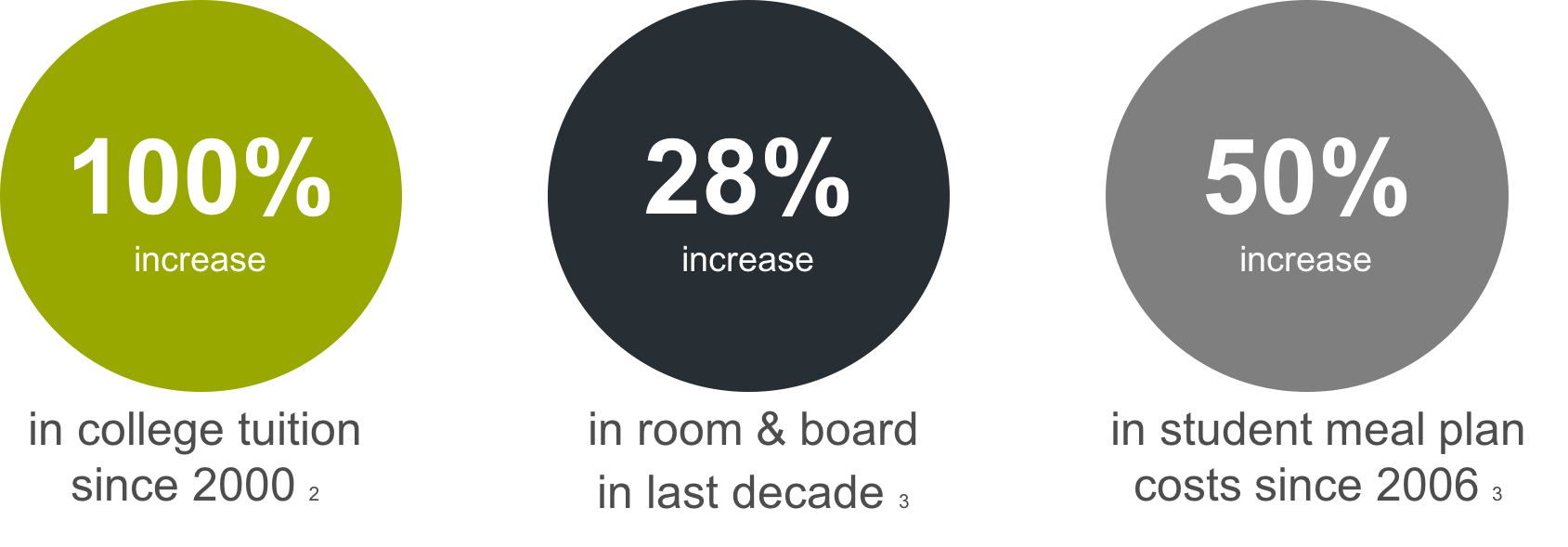

Consider the following statistics regarding the costs of higher education:

It shouldn’t be a big surprise that 83% of Americans say they can’t afford a college degree for themselves or a family member.

With tuition, class materials and student fees being inflexible fixed costs, students are opting out of meal plans–or buying the bare minimum–to save money. In addition to declining meal plan revenue, campuses are now also battling double-digit levels of food insecurity* among students.

According to a recent food insecurity study of college students[4]:

- 47% of students enrolled at four-year colleges say they experienced food insecurity in the last 30 days.

- 43% of students at four-year colleges and enrolled in a campus meal plan say they experienced food insecurity in the last 30 days.

*Food insecurity is defined as the state of being without reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.

WHAT WE THINK

The projected financial reality of future C&U students and their families makes changes to dining services inevitable.

The desire for quality, nutritious and delicious food is universal among students. But the average college and university charges about $18.75 per day, for a three-meal-a-day dining contract, compared to the less than $11 a day a single person spends for food[5]. As the number of financially stressed students who see cost as a barrier to selecting a meal plan that fits both their budget and hunger state increases, so do the risks to current C&U dining services models.

WHAT’S NEXT

It’s important to proactively anticipate these conversations and be prepared with both product and business solutions to help foodservice directors navigate this next evolution in C&U dining.

Consider the case of Jerry Rackliffe, Georgia State University’s vice president for finance administration:

After seeing the research on financial need and graduation rates, he convinced the housing department to open a “tiny-dorm” option that would include smaller rooms, more basic amenities and an unlimited meal plan that would collectively cost less than a room alone at other upperclassmen units. When Patton Hall opened in the fall of 2009, it filled up faster than any other campus housing option. It was so popular, the school converted two local hotels to the same concept in 2011.

A basic-tier plan that provides unlimited meals could be a mutually beneficial solution: increasing meal plan participation among financially at-risk students and relieving pressure from stop-gap hunger solutions like food banks and student meal donations.

Just some Thought for Food™

[1] “Why Universities Are Phasing Out Luxury Dorms.” The Atlantic. August 21, 2017.

[2] “Tuition and Fees and Room and Board Over Time.” The College Board. 2016

[3] U.S. Department of Education. 2017.

[4] “Hunger on Campus: The Challenge of Food Insecurity for College Students.” Dubick, Matthews and Cady. October 2016.

[5] The Hechinger Report. 2016.